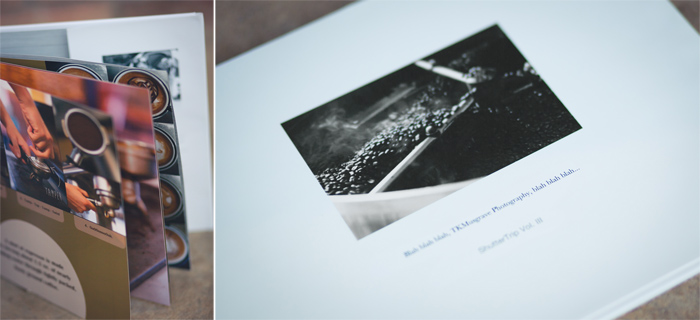

Origins • Roasting • Extraction • Latte art

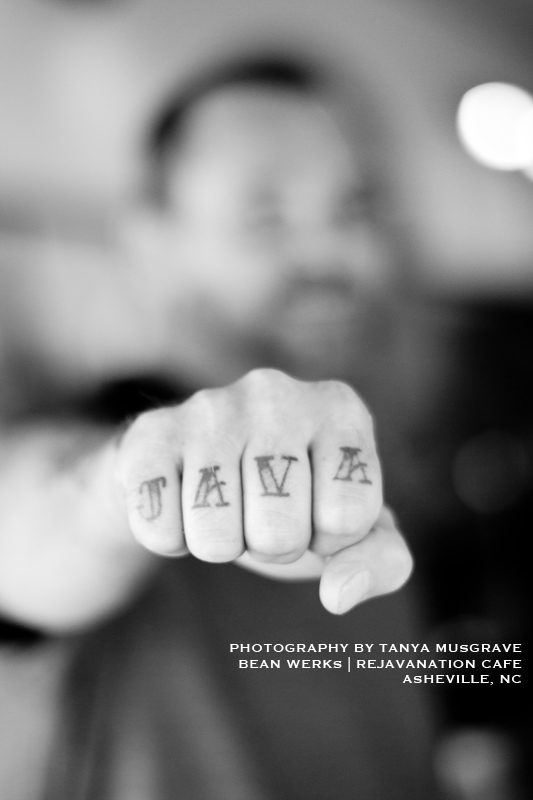

I took a detour as a barista in Asheville, NC a bit ago -- most fun I've had in a day-to-day job. I got learnt the basic ways in coffee, so I thought I'd pass on the fascination.

For the coffee-lover, the curious, the cultured-- or simply the wannabe connoisseurs ready to take that first step towards coffee snobbery, this is for you...(Though technically I made this for my mom -- design similar to the Vanilla Cycles book I made for my brother)

"You wanna pick up the order? It's a local roaster on Haywood." That's how the idea percolated (see what I did there) -- and spurred this as my next ShutterTrip.

Skip ahead where I spend nearly five hours hovering over Eli Ornberg as he artisan-roasted his way onto my list of small-town heroes. He loved teaching, so I took advantage. Yes I'm nerdy enough, yes I took notes. Get ready to learn...

~Divertitevi~

This was the first time I'd ever seen green coffee beans...

The beans are checked for their moisture content to ensure the roaster is getting a fair deal. The moisture content for most beans usually starts at 11-12%.

Anything below 10.2-ish% would be considered a rip off. However, other factors like humidity could affect the beans before they're put into the sensor. Great care in transport and storage must be taken.

Sometimes when the seeds finish with a wet hulling process, the "normal" moisture content is 13%. Artisan roasters must have extensive knowledge of the many types of beans (different origins and climates, hence different processes). The Bean Werks Coffee Co. works with over 60+ kinds of beans.

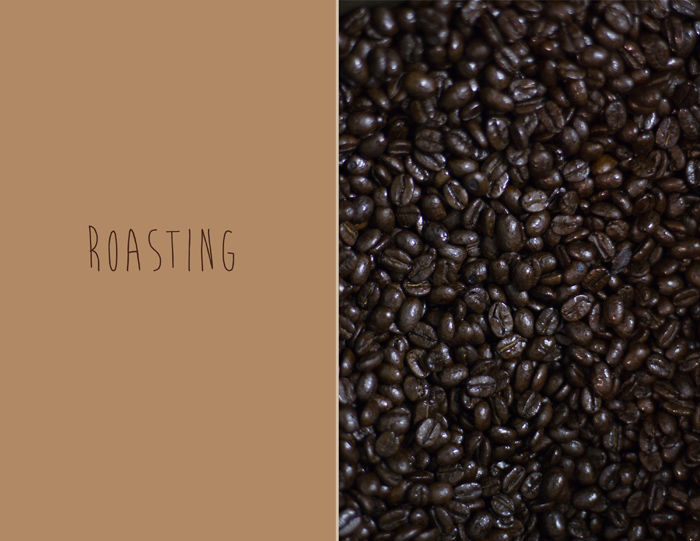

1. The drum is "charged," or warmed. Opening the dump door helps it heat up faster by feeding the drum more oxygen.

2. Twenty to thirty degrees are lost when green beans go in.

3. The beans are roasted at specific temperatures according tot heir bean type (their place of origin). Some batches have more of a "roasting profile" rather than a specific bean profile. For example, some can't go below a certain temperature, and some can only be roasted in small batches.

1. The beans start "popping." When the artisan roaster first hears this, it's called the "first crack."

2. He constantly checks the color, oils and "road maps." The longer you roast, the more oil surfaces. "Road maps" are the little lines that can be faintly seen on underdeveloped beans.

3. He'll test them by crushing a sample; a good bean will crack, whereas a burnt one will disintegrate.

The lever on the side will direct air flow to either roast, or pull chaff out (which loses temperature. When set in the middle, it pulls chaff as well as roasts. About 5 minutes in, the beans start to cook each other. The artisan roaster must balance the temp and time, while also keeping an eye on the appearance of the beans.

The cooling process is almost as important as the roasting process -- the beans must be brought down to a cooler temperature as soon as possible so they don't continue to cook. The cooling unit accomplishes this by stirring them above the built-in cooling fan.

Careful charts are kept for each batch and roasting profile.

The batch (weighed before-hand) is weighed again, and categorized as a light, medium or dark roast.

The difference between light and dark roast is actually determined by the percentage of weight loss.

Around 14.7% weight loss would be a light roast. Anything above 18% is considered a dark roast (weight loss above 22% is considered garbage). Sometimes there are only minutes of roasting between each percent.

Example of Columbian beans in various stages.

Roasters/baristas/coffee connoisseurs will "cup" coffee frequently, meaning they will evaluate, compare and take detailed notes about the flavors. Eventually, an experienced cupper will be able to place flavor traits in different origins and geographical locations. The goal is to build a "reference library" via palate, so the cupper has extensive knowledge in judging quality, processes, and of course, new coffees.

Cupping is definitely a social thing and is best done in a group -- where opinions and notes can be compared.

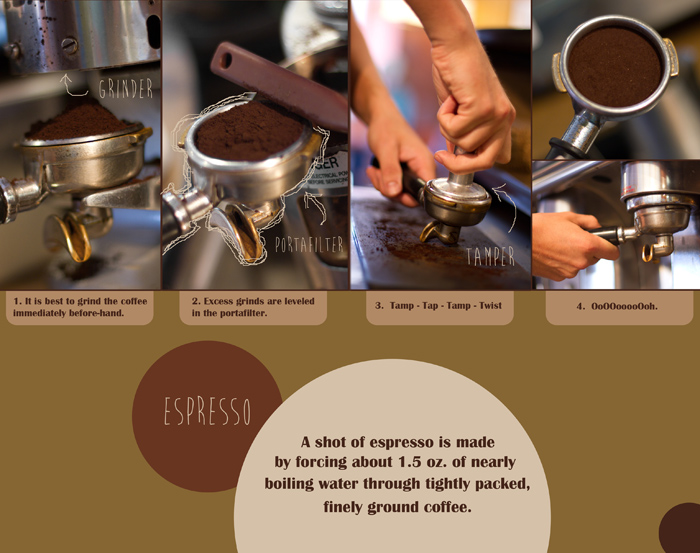

Portafilters...

Poured latte art was something I aimed to perfect while I was there but uhhhh -- come to find out, it was a lot harder than I thought.

Pouring designs is more complex than it looks -- the barista must steam the milk very skillfully in order to get it to produce perfect microfoam for pouring. Good milk, steady hands, technique, and lots of practice will determine the quality of the pour. See the difference for yourself. *Shame*

However I got the hang of etching (real baristas would probably scoff because it's actually a heckuva lot easier than pouring). Etching is usually performed using a coffee stirrer or a small dowel of sorts.

These patterns generally have a shorter life-span than poured designs because the foam dissolves into the latte more quickly. But etching also allows a little more versatility.

And there you have it! One small step towards being that awesomely annoying coffee snob ;-) You're welcome.