I was chatting with Zarena and playing with little Sautesh on the porch of tent #23 when Sarah came weaving through the gravel walkways to find me.

"Tanya, you have to come and talk to this man!"

"I came to find you while there's still a translator available." We bid goodbyes and she fills me in on the way to the main building.

"He's incredible and a huge supporter of women. He was so proud of his daughters and was showing us photos and videos of them fighting in the military!" My interest was definitely piqued, since it seemed we'd been surrounded with a differing view of women for a bit now.

The refurbished cosmetics and pharmaceutical factory stands at the center, tents shown off to the left. (Update as of April 2017: tent families have now been able to move inside, thanks to a construction project that moved single men into a dormitory-style space upstairs)

Dismal hallway walls before St. Ethelburga’s Centre for Reconciliation and Peace came in from London to head up a painting project where residents were able to express themselves. (Update April 2017: Construction projects have outfitted the rooms with doors and ceilings.)

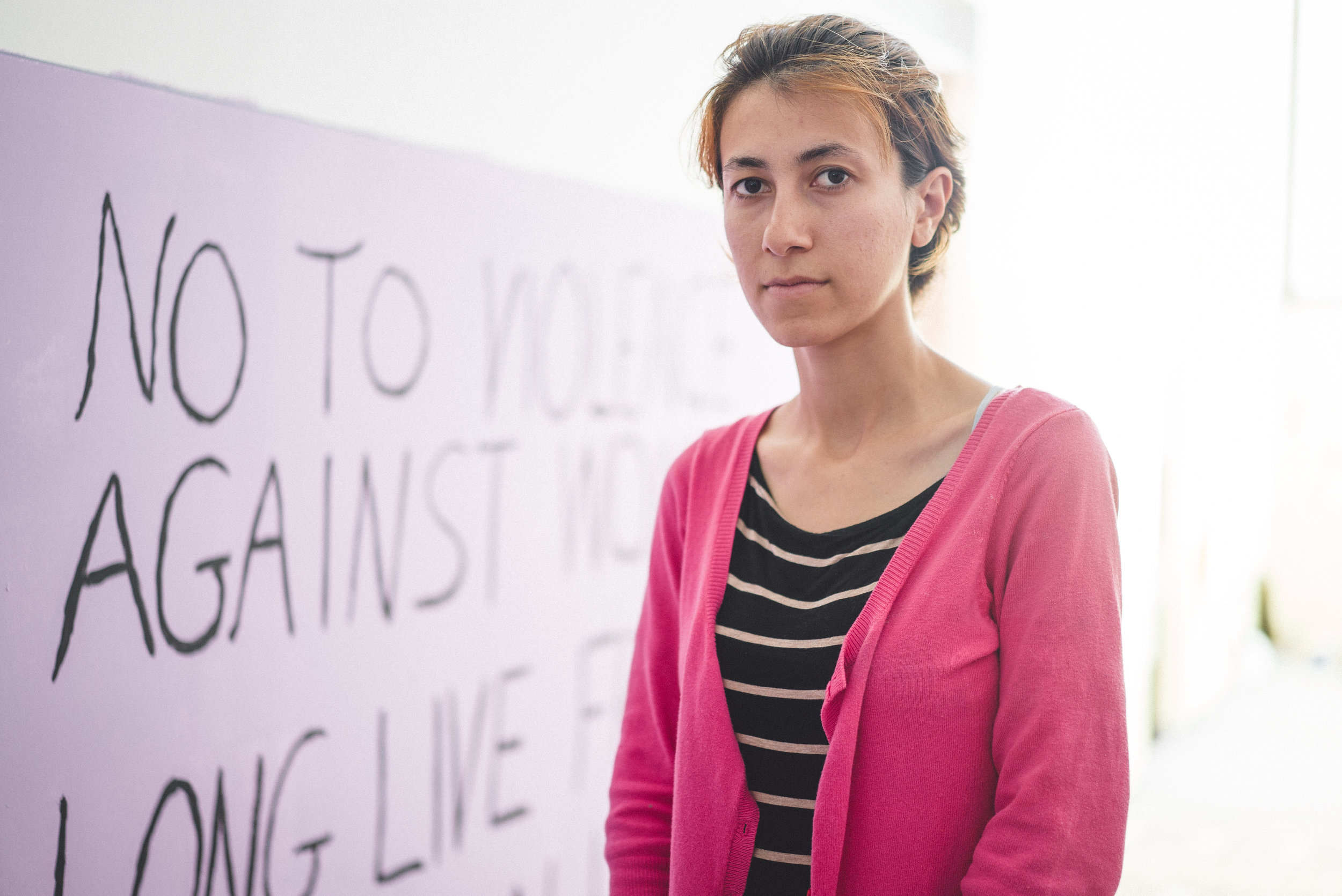

We enter the building and make our way down the hall. Cubicles were built in a rush to accommodate families (approximately 12' x 12' in size); we walk past rooms, making turns here and there until we come to one in particular. It is painted a pastel purple with a bold voice cathartically sprawled across:

"NO TO VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. LONG LIVE FREEDOM AND EQUALITY."

Half of a wooden pallet leans across the curtained doorway making a makeshift baby gate. In a shuffle to remove shoes and greet one another, I say a quick farewell to my guide and a hello to my translator, Nazgol. She's from London with a group that's heading up the painting project in the camp that's an interesting story in itself. I learn quickly that her eloquence in translating Farsi is positively invaluable.

Masoud greets us with a boisterous personality, his tipped mustache and laugh wrinkles immediately put me at ease with a positive spirit.

Masoud with granddaughter, Nila. Something so little as seeing Masoud's twinkle appear when he sees any woman exercising some defiance, (if only to snag a ladder from the male workers to photograph from a higher angle) makes me want to make them proud.

"It was in the middle of December when I was waiting for my firstborn. It was a women's hospital so I was standing outside for 3 days. They would give me news on how my wife was doing throughout the labor. On the 3rd day, my sister-in-law came out and I said 'Tell me what happened, what's going on?' She wouldn't tell me anything and I was getting worried, wondering what happened to the child and whether or not the child was okay. Finally they came out with it. 'It's a girl.' I got angry. I've been worrying about whether or not this child is healthy or whether she was even born properly and you're telling me she's a girl...that's it? It's an old way of thinking—it made no difference to me whether they were boys or girls. As an enlightened mullah (Persian for "scholar") I could love them in this way."

Masoud has two children—both daughters.

"In Iran, there's always a focus on boys—at a wedding, they will bless you by saying 'May God give you a son.' A woman is slightly defined by the men in her life—'She has a good father, her brother is an honest man...' Sons will get a larger inheritance, and when you're standing in court as a woman, you need two witnesses while a man only needs one."

His daughter, Gashin, chimes in. "Women are perpetuating the cycle too—it's the woman's choice to cover up, but you don't get as much respect when you wear what you want. When female volunteers come, the men will act and behave in a way that says 'We're just like you—let's hug and take pictures.' Women won't necessarily even talk to the men, or they're reserved and scared because of what the husband might say."

Masoud continues.

"I realized 30 years ago that I wanted nothing to do with Islam—I got involved with politics around age 12 and my elders guided me as a teenager. We read a Kurdish poet named Ghaneh who wrote about the working class, the poor, and the power of women, their strength, and how far they can go. Islam considers this poet is a communist. But "communism" in the east is very different. This isn't the communism where there is no God. I believe in a God—I believe these things aren't coincidences, the way your veins work, the way that there's skin on your hands to protect you—it's not atheism. There is a belief in something—it's very important to differentiate and not put the European definition of "communism" on us."

He brings up a video on his phone of a lively Kurdish celebration dance that is done as a group, men and women. Kurdish culture, from the very beginning, always included men and women being together. With the coming of Islam, these kinds of activities became segregated, however the left-wing Kurds brought it back into existence.

"Women can take their own rights...they do not need a man to do it for them...sort of a Beyonce-feminism." (lol—that brought about good laughs).

Masoud, 47, shows a video of a celebratory Kurdish dance to Nazgol—his daughter Gashin in the background.

Masoud is from Iranian Kurdistan, here with his wife, Nasrin, daughter, Gashin, her husband and daughter, as well as Gashin's younger sister Yasaman, who we'd passed painting in one of the common rooms.

"I was working undercover for 8 years as a Freedom Fighter (In Iran, any group that is politically opposed is seen as a national security threat and is not allowed). When I found out the Iranian government knew and that they were coming to get us, we left for Iraq where we lived for 5 years. Our aim was to get to Germany, but when we arrived here in Greece on March 4, 2016, the borders closed a few weeks later and we couldn't afford the smugglers to continue."

Now here again, the term "Middle East" was a gigantic nebulous region to me, so in case there are others who are in the dark about Kurdistan and what it means to be Kurdish, let me break it down for you like they were so kind to do for me.

1. Kurds are the largest ethnic group (~25-34 million) unable to govern themselves.

So they have their own culture, their own history and beliefs, but have never achieved an official nation state.

2. Kurdistan basically isn't official, but it exists....ish.

The Kurds inhabit a region straddling Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Armenia and have taken to calling it "Kurdistan." So imagine if you will, if Mexico got dropped in the middle of the United States—a vast population split into different states, with each state having laws (varying in leniency) that still deny permission to govern themselves.

3. You know that badass group of women that fight against ISIS? Dems Kurds—specifically Peshmerga.

A friend once told me "If I were in any trouble at all over there, I'd call the Kurds." They've been a strong ally to the US in the fight against ISIS. It's not black and white—there are extremely complicated politics that exist within and involving the Kurds from all the different regions, but should you want to read more about who the Kurds are, this article from the BBC helps break down the alphabet soup of the KDP, YPG, PKK, SDF, PYD, and KNC (armed groups and political parties).

"Peshmerga" means "the one who takes a step and goes beyond death" "those who face death" or "one who confronts death." It's the armed forces of the Iraqi Kurdish and within it there are different groups, which include the groups of women who fight ISIS.

These groups may have differing political opinions, but they are united as one front and known collectively as Peshmerga. The main core of the opinion is to speak against the oppressive and to fight for the rights of humanity no matter who it is.

4. TL:DR - A brief and simplified history of the Kurds in Iraq

In the 80s, Saddam attacked the Kurdish town of Halabja—chemical weapons, sound familiar? It killed 5,000 Kurds. The U.S. pushed him out, trained Peshmerga, and established a no-fly zone and an autonomous Kurdistan region within Iraq (hello allies). They have more rights there in Iraq; functioning, but not completely separate. In terms of the rules that they live by, their society and legal rules, they run their own show. However, there are still major complications when it comes to money and oil in connection with Baghdad, and their money has been cut off. Why? The government is worried that if the Iraqi Kurds have more autonomy, the Turkish, Iranian and Syrian Kurds will want the same.

No country wants them to separate—that's why people are attacking Kurds and it's why they're fighting back.

Note: Remember that I'm talking to left-wing Kurds—there are two sides to every story; do background reading. But I will say that when I Googled "right-wing Kurds," one of the top results brought the question, "Do they even exist?" With their background and present situation, I'm trying to figure out what that would even look like.

They pulled up photos of where and who they'd been in just the past few years.

Gashin, Masoud, and Yasaman - 2013

Gashin and her husband, Faryad - Jan 2015

At about that time, the tea arrives, bringing me back to the small cubicled reality. Masoud offers sugar and we laugh as I explain the concept of southern sweet tea. He jovially pushes the sugar closer to me, welcoming full use of the scoop.

They pause to ask what I'm writing all this down for, where this is going. I mention my friend circles and people like me who aren't really aware of things going on; after all, our presence in the camps wasn't really intended to be a political statement by any means—it was just to help, and to learn.

Gashin speaks up, a voice stronger than what I'd been accustomed to hearing from the women in the camp. She was a journalist back home with a degree in mathematics (no pressure Tanya).

"The reason we're here is because of politics. In that region, you can't detach from politics, you are defined by it. Our story is political. Our existence is political."

So now what? What is their present situation?

Gashin had met with a Greek lawyer days before, asking him about the future. "What are our choices?—We don't have money to support ourselves, where are we to go from here?"

He replies, "The money issue shouldn't be your focus right now—the first issue is that you are safe."

"Yes that is right, but what is this life? You cannot move forward in life if you don't have money or support. Housing, citizenship, etc., you need support, you can't just live like this."

They never got an answer. She continues her frustration, "Some of our friends got citizenship here in Greece and they went out but they have no job and don't have money." (Remember that sucky Greek economy? 23% unemployment rate.)

"If we go anywhere, we're all going to be working and contributing. It's not that we're going to go there and just eat and sleep. The only thing that closing the borders did was make more smugglers. It became a money game and was counterproductive."

For a limited amount of months, Mercy Corp pledged to give out cash cards—€70 to the head of household and €50 per family member with a cap of €340 per family per month (Update as of 4.18.17 - the cash cards have been continuing)

In the meantime, it can be difficult to find anyone in the camp that sees eye to eye. "We do have very different opinions and it's hard to be in this situation where there's no one we can relate to. Most people here are Muslim, but there are also people here within the camp who aren't, but are too afraid to actually say it. Especially within bigger communities of people, it would have a large impact on their lives. But we're not afraid to say we're not Muslim."

Another piece of the fallout actually involves her little sister Yasaman. She was in year 10 when they left for Iraq a week before exams. In Iraq she was put back a year and when she couldn't read Arabic, fell behind another year. Leaving to come to Greece, she's fallen behind 4 years of education.

What do you want to say to the world?

"Do not let the oppressors have a presence or go forward any more; stand in the way. Stop them. Whether they're oppressive religiously in Islam, or dictatorship. -Masoud

Where are the human rights defenders that they can't hear our voices? Are they not on this planet, or are we not on this planet. Do they not exist, or do we not exist—it's one or the other.

The fascist regime has ruined enough of our lives and we just want to get out of here and not waste any more time. We want to work, we want to live our lives. We will leave whether it's a legal or an illegal way." -Gashin

Truly helpless?

A lot of this doesn't affect me personally, so it makes sense why any knowledge or education of this wasn't forefront (not a bad thing, just reality). It was once I met them that I began to care. I've always been one to sidestep political debates mainly because I abhor division and also because I didn't really know what I was talking about. But it's an odd phenomenon—once you befriend and care for someone, it brings about the knowledge and education needed to be able to care for them better—because now it does affect me personally.

Nazgol, my translator, said later, "Someone once said to me that true knowledge is that which touches both the heart and mind because it is only that which touches both that paves a place in your memory. True knowledge differs because it causes a shift within you; it’s different to that which you have intellectually accepted and understood."

Your first step might look like mine—to meet people and start caring.

Update as of 4.18.17 - Masoud and his family are still within the camp.

One thing you can do to help: A doctor friend of mine has been involved with refugees from Lesvos and now to Iraq where they are building a hospital in Mosul (Iraq, right next to Kurdistan). You can see their live FB video and a Peshmerga friend of his. If you'd like to donate to the cause, go here.